KBOO 6 November 1986

Tit for tat, payback, retaliation, whatever you want to call it, a child’s game or a national way of life, recrimination goes on and on and the world suffers.

You see it on the soccer field where one bit of foul play leads to another and soon the whole spirit of a game deteriorates and players are sent off. You see it on the international scene where the victims of one incident are the perpetrators of the next or where verbal exchanges become increasingly heated or there is an escalation of expulsions. It is all so unjustified – and so unproductive. How right Mahatma Gandhi was when he said, ‘An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.’

Some visitors to town encourage me to think it needn’t be that way. We have just had staying with us a couple who have every reason to blame and be bitter but have broken what they call ‘the chain of hate.’

They are Tianethone and Viengxay Chantharasy from the small Southeast Asian nation of Laos. Tianethone was Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the last coalition government in his country before the Communists took over in 1975. He is now Secretary-General of the United Lao National Liberation Front. The struggle for freedom is not new to him for already in the 1940s he was enrolled as a young man in his country’s army of National Liberation.

The Chantharasys could justifiably hate the French, the Americans, the Communists, and especially the Vietnamese who today occupy Laos and have killed 10,000 Laotians in concentration camps and are trying with forced marriages between Vietnamese and Laotians to create a new race. But they have chosen not to. ‘If you have hatred against your brother,’ Tianethone asks, ‘how can you liberate your country?’

Naturally, this liberation of their country from foreign domination is a priority for them. They believe it will happen one day, though it will be a long struggle. ‘Many of us will have passed away before liberation,’ he says. And it will likely be achieved, he feels, by political rather than military means. The wellbeing of their fellow refugees is a constant concern. There are 92,000 Laotian refugees in camps along the Mekong River and 350,000 scattered all over the world out of the country’s former population of 3 ½ million. The Chantharasys live half of each year in Thailand to be able to help their people. ‘Our presence in Thailand is a morale booster,’ says Tianethone. They have personally taken responsibility for several orphans and they want to raise money for the medical and clothing needs of the refugees in the camps.

I was present when they met a crossection of people from Oregon at various occasions and when they conferred with some fifty Laotians now living in the state. I noticed, as others did, how free of bitterness they were, and their passion to win back their country is matched by the desire to create a Laotian society in the future that would be impervious to takeover.

‘We must have the insight to see beyond the liberation of Laos,’ he told his fellow countrymen and women, ‘because we have seen in Uganda and in many other countries that after liberation there has been a change of power but the bloodshed continues. We need to start on a new basis and build trust, confidence, love, and respect for different tribes and ethnic minorities.’

I was struck, too, that despite the weight of their country’s problems they were concerned both with the needs of the world at large and with the individual in front of them. It is too small to think only of your country,’ he said. ‘Peace or freedom are indivisible.’

Their breadth of approach they owed, they told me, to the change that Moral Re-Armament had brought into their life many years ago. At that time, Viengxay said, there was so little communication in their marriage that she had one day opened all the windows and doors of her house in a dangerous part of the country in the hope that robbers would break in and kill her and her children. But when her husband attended a Moral Re-Armament assembly in the United States he had written her a letter that was honest about what he did behind her back and asked her forgiveness. She in turn asked forgiveness for her bitterness. A great happiness had come into their marriage and on that sound foundation they had developed an effectiveness together in all areas of life.

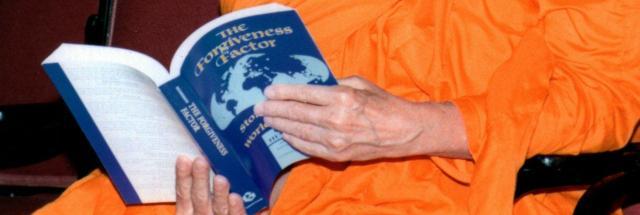

They had learned to listen to their inner voice and to follow standards of honesty, purity, unselfishness and love which, he said, were not very different from Buddhist principles: ‘We have to put into practice what is taught by our Buddhist religion.’ Viengxay is quoted in ‘The Oregonian’: ‘The secret of Moral Re-Armament is the quiet time, to listen to your inner voice and to share. We think that changing ourselves is every important. We share these ideas to our friends in the resistance. They have to be freed from hatred and bitterness because many are sick from the suffering.’

The Chantharasys are alive today because of their generous approach to all and their effort to reach out even to those who disagree with them. While Tianethone was in the coalition government he and Viengxay were working to lay this new moral foundation in their people. A young leftist militant observed them and was attracted by what he felt was a universal approach.

One day in May 1975 he went to a cell meeting and discovered that Chantharasy as a nationalist minister in the government was on the list for arrest that night. He rushed to the Chantharasy home and persuaded them to leave. The Chantharasys packed a few belongings, got the permission of the prime minister to go, left by the back door, and crossed the Mekong River into Thailand. Fifteen minutes later the Pathet Lao soldiers arrived to arrest them.