Foreword to Ice in Every Carriage

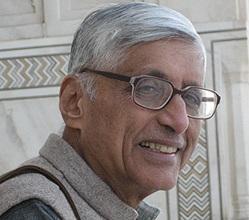

by Rajmohan Gandhi

‘A different accent’ was the title of a long-running column in the print media by the author of this book, Michael Henderson. His British accent certainly stood out in the USA, where Michael lived for many years, but the difference his writing brings is larger, for his accent is always hope-giving and reconciling, and challenging as well.

Here, in this study of an unusual activity that took place in the early 1950s, Michael provides a historical accent. I should say he continues to provide it, for this intriguing slice of history is a natural sequel to See You After the Duration, Michael’s story from the 1940s of British children, of which he and his brother were two, who were sent for safety to North America in World War II.

Here, in this study of an unusual activity that took place in the early 1950s, Michael provides a historical accent. I should say he continues to provide it, for this intriguing slice of history is a natural sequel to See You After the Duration, Michael’s story from the 1940s of British children, of which he and his brother were two, who were sent for safety to North America in World War II.

What Michael records in this book is the creation of what at the time appeared to be an unthinkable bridge between seemingly antagonistic cultures – between a West obliged to leave its colonies and an East excited by the triumph of its freedom movements. An initiative in 1952-53 into India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka led by an extraordinary American (of whom not many know), and joined in by scores of ‘ordinary’ and mostly Western women and men, built that bridge. The twain of East and West met, quite cordially.

Michael tells what I think is a historic story. True, westerners and easterners had been ‘meeting’ for centuries. During European rule over the rest of the world, exotic Orientals or Blacks were often seen in the West. Usually they were slaves or Rajas or students. And (appearing equally exotic to the East), European teachers, nurses, missionaries, policemen, soldiers and officials were visible in the Orient and in Africa.

Moreover, inter-racial marriages occurred now and then and made news. These were exceptional events, usually frowned upon by the ‘community’, which meant either an Asian or a European group, or two separate groups, never a mixture.

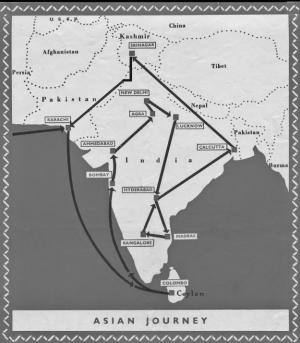

What took place in South Asia in 1952-53 went beyond isolated (and no doubt often quite deep) relationships. What occurred - within five years of independence - was that a very large number of Indians, Pakistanis and Sri Lankans, in more than a dozen different South Asian cities, found that they could interact naturally, normally and warmly with a party of nearly 200 Westerners. And vice versa.

What took place in South Asia in 1952-53 went beyond isolated (and no doubt often quite deep) relationships. What occurred - within five years of independence - was that a very large number of Indians, Pakistanis and Sri Lankans, in more than a dozen different South Asian cities, found that they could interact naturally, normally and warmly with a party of nearly 200 Westerners. And vice versa.

Earlier large-scale encounters between East and West had only taken place on battlefields. The encounters that Michael records took place in theatres, auditoriums and foyers, and also in homes, campuses and reception halls. Asians laughed at what Europeans also found amusing. They cried at what saddened Europeans. They found that what pricked European consciences was the sort of thing that also needled their consciences.

And when Westerners spoke (or sang) about their hopes and fears, or about their rivalries and hates, or their difficulty in admitting that they done something wrong or hurt someone, or their joy when brother embraced a long-alienated brother, Indians, Pakistanis and Sri Lankans felt that their own life-stories were being enacted in front of them.

Skin-colour ceased to matter. Religious labels lost their power to divide. History was forgiven. And in thousands of hearts a voice spoke, ‘We are the same underneath.’ And when the easterners who went to the shows and the westerners who produced them met face to face – in small or large groups or one on one - there was another recognition: ‘We are equal.’

The hard-won freedom that South Asians savoured with pride in 1952-53 meant dignity and equality with the West. It could so easily have also turned to hostility. The venture that Henderson describes prevented potential hostility and produced fraternity.

The hard-won freedom that South Asians savoured with pride in 1952-53 meant dignity and equality with the West. It could so easily have also turned to hostility. The venture that Henderson describes prevented potential hostility and produced fraternity.

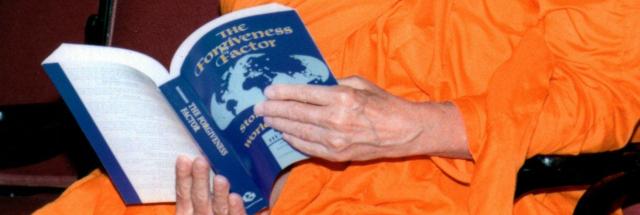

The venture also sowed seeds of honesty and reconciliation in God knows how many hundreds, possibly thousands, of hearts. Russi Lala’s personal account, in the afterword to this book, of what happened inside of him after he witnessed one of the plays enables us to imagine the stirring that was produced in a great many Indians, Pakistanis and Sri Lankans.

And what a logistical feat the venture was! To think, in 1952-53, of hauling the battalion-size and by no means innately harmonious party and its ENORMOUS stage equipment first across oceans and then across a huge land-mass was not a rational idea.

Fortunately, the audacity paid off. A seemingly weird whim (or was it inspiration?) triumphed. Though I did not run into the party at the time (as a student in Delhi, I had heard echoes of what was happening), my guess is that matters were helped by the readiness of the men and women in the party to (a) laugh at themselves, (b) put the other person first, (c) work non-stop, and (d) pray.

I should confirm another result to which Henderson refers. The venture produced a leap in India’s drama technology. This is what I heard myself from the lips of Prithvi Raj Kapoor, the greatest name, perhaps, in modern Indian drama. The Indian stage was not the same after the possibilities revealed by the shows in 1952-53.

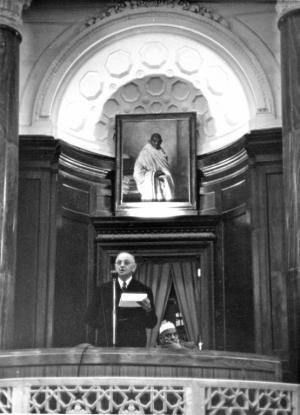

And let me also record what Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, once told me in her home in Dehra Dun. She said that her brother, the Prime Minister, was moved to tears in New Delhi by the superb singing of the Indian national anthem by the international chorus.

But I want to go back to the unearthing of our sameness. The 1952-53 interactions that Henderson records anticipated - provided a foretaste of - our 21st century world. I think it is not unreasonable to see the interactions as crucial forerunners of the current dialogue between civilizations, religions and cultures, and as the start of the coming down of high thick walls.

I don’t think Michael, or someone like Lou Fleming or Jarvis Harriman, who helped him immensely with this work, wants to claim that this is a bias-proof or error-proof record of what happened. Much of it is based on memories, and we all know of the little tricks these play. No one should read this story either as a complete account or as a precise record of who did what where. It is more than likely that it leaves out some significant events, known only to participants who are no more.

I don’t think Michael, or someone like Lou Fleming or Jarvis Harriman, who helped him immensely with this work, wants to claim that this is a bias-proof or error-proof record of what happened. Much of it is based on memories, and we all know of the little tricks these play. No one should read this story either as a complete account or as a precise record of who did what where. It is more than likely that it leaves out some significant events, known only to participants who are no more.

Though not a complete account, it is a priceless record of a bold, multicultural initiative by civil society at a time when people did not use such phrases. And it is proof that history is often made by people usually missed out by historians.

A question however assails me. Many in India and the West may have come together today, but what about the walls that remain? What about relations between the West and the Muslim world? Or between Africa and Asia? Or between Asia and Latin America? Who today are the ones eager to catch a weird inspired thought and to work together to implement it?

Anyway, I believe I speak for many when I say, ‘Thank you, Michael.’

Rajmohan Gandhi

Urbana, Illinois, 11 August 2009